NEWS

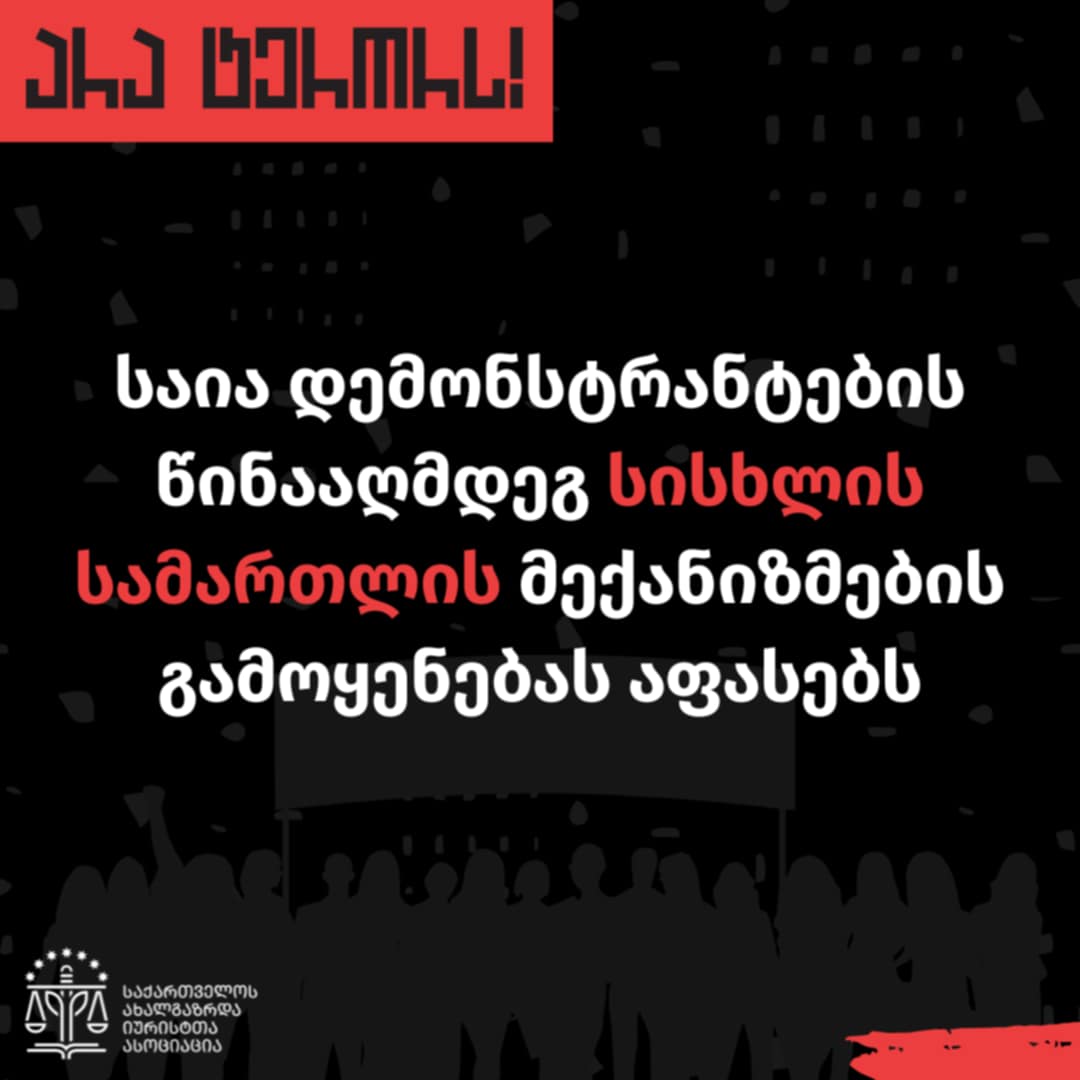

Alongside other mechanisms of repression, the use of criminal justice mechanisms against protesters and civil activists has been increasing throughout 2024, with the goal of suppression of dissent.

GYLA is monitoring ongoing criminal cases involving at least 50 individuals related to the protests. The monitoring includes the cases of 6 individuals detained in connection with the Russian law protests in April-May 2024, 38 defendants arrested during the ongoing legitimate protests after November 19 and 28, as well as the cases of Balda Canyon activist Indiko Bzhalava, activist Vitali Guguchia, and activist Ioseb Babaev.

1. Criminal Charges Brought

The following charges have been brought against the activists: organisation, management and participation in group violence (Article 225, Part 1 and 2 of the Criminal Code), harming the health of a police officer in connection with their official activities (Article 3531, Part 2 of the Criminal Code), damage or destruction of property by a group of persons (Article 187, Part 2 of the Criminal Code), etc. Opposition politician Aleko Elisashvili is accused of persecution committed with violence or threat of violence (Article 156, Part 2 of the Criminal Code), and several activists are also charged with drug-related crimes (charges under Article 260 of the Criminal Code).

Case Delays

The consideration of cases of individuals arrested during protests against Russian law is being delayed. In the majority of the cases mentioned, the evidence is declared indisputable by the defence, yet the court does not finalize the consideration of the case and repeatedly postpones hearings for extended periods, citing various reasons. According to GYLA’s assessment, the Prosecutor’s Office of Georgia and the Tbilisi City Court appear to be intentionally delaying the proceedings, seemingly aimed at preventing President Salome Zourabichvili from exercising her constitutional power to pardon the activists. Such an attitude by the prosecution and judicial bodies once again raises concern that the ongoing criminal cases against the activists are not free from the motives of alleged political persecution. This stance is alarming and undermines, on the one hand, the work of the Prosecutor’s Office as a constitutional body, and, on the other, the functioning of the judicial system.

The Practice of using Detention without considering the Individual Characteristics of the Defendants

At the initial stage, the court imposed the most severe preventive measure – detention – for all activists detained during the protests against the Russian law and during the rallies in November. In all cases, the court fully granted the prosecutor's motion to use detention - disregarding such circumstances of the defendants as: their individual characteristics, their personality, work, age, health condition, family and financial status and other relevant factors. In addition, among the detainees were persons under the age of 21, students and people from socially vulnerable families. Some were sole breadwinners or caregivers for family members with health issues. The majority of them had no previous convictions and/or records of administrative offenses. The prosecution justified the use of detention by citing generalized risks, such as the possibility of absconding, destruction of evidence, or committing a new crime - none of which appeared to be substantiated by the individual circumstances of the defendants.

Only in two exceptional cases was detention replaced with a less severe preventive measure. One involved politician Aleko Elisashvili, and the other concerned a detained underage activist. In both instances, the prosecution itself petitioned for the change. In the first case, detention was replaced with bail, while in the second, the underage activist was released under parental supervision.

The Standard of Probable Cause

Defence laywers consistently emphasized the absence of evidence that would meet the standard of probable cause required for a criminal charge. Specifically, in cases charged under Article 225 of the Criminal Code (organisation, management and participation in group violence), the circumstances presented during hearings often failed to demonstrate coordination or collective action among the defendants, as required by the probable cause standard. For some defendants, the charges were based on isolated actions carried out at different times and locations, without evidence of mutual knowledge or intent.

The prosecution accuses individuals of acts such as throwing objects (sticks, bottles, cardboard rods, or unidentified heavy items), but fails to connect these actions to collective violence or address specific damages caused.

It is also noteworthy that a defence laywer of one individual pointed out that they had handled numerous administrative cases involving similar acts, where courts classified those actions as administrative offenses. They expressed confusion over how the prosecution distinguished these actions from administrative violations in this case.

For instance, where was the line drawn between an administrative offense and a potential crime while throwing a stone or a stick?

The actions charged under Article 225 of the Criminal Code of Georgia are alarming not only in terms of the standard of probable cause applied to specific defendants but also in assessing the risks involved. These risks include the potential misuse of criminal mechanisms by the prosecution, which could turn into a tool for restricting freedom of expression and persecuting protest participants.

Cases of Ill-Treatment

Several activists detained under criminal proceedings reported instances of ill-treatment during their arrest, transportation, or while in detention. For example, Aleko Elisashvili stated during his first court appearance that he was placed in a vehicle during his arrest and beaten.

Saba Skhvitaridze provided a detailed account of his experience of torture and inhuman treatment. According to Skhvitaridze, he was detained by the police on the highway to Zestafoni without being informed of the grounds for his arrest or given the opportunity to contact a lawyer. He was subsequently handed over to an unidentified operational group near Gori and transferred to the police department in Dighomi.

At the Dighomi police department, on the fifth floor of the building, four masked individuals physically assaulted and beat him. Later, on the eighth floor of the same building, another individual wearing a patrol police uniform and a mask, along with other persons, subjected him to further violence.

Revaz Kiknadze stated that he was subjected to psychological pressure and verbal abuse to force him to confess to a crime and accuse others, being told that doing so would result in a more loyal attitude toward him from the system.

The information provided by the defendants to the court, along with other similar accounts, reinforces the fact that torture, inhuman, and degrading treatment of individuals is systemic and large-scale.

Inaction of Special Investigation Service (SIS)

It is alarming that, to date, there has been no proper investigation into the abuse of power by law enforcement during protests against the Russian law, nor during the subsequent protests from November 28th, nor any identification of those responsible.

The systemic inaction of SIS in relation to crimes committed against demonstrators and journalists indicates the SIS’s complicity in this violence.

GYLA continues moniroting of the preliminary hearings and hearings on the merits of the ongoing cases and will periodically provide public with updated information.

SHARE: